What does anti-Indigenous racism in healthcare look like in Canada?

A new report spotlights some long-standing truths using recent research from BC. We ground those findings in examples from across the country.

Hey there, and welcome to the eighth issue of The Supplement, a newsletter that fills in the gaps of your other news intake. This is Alex, one-third of the Supplement team!

Each week, we pick a question submitted by you, our readers. If you’d like to submit a question for a future week — it can seriously be about anything — then email us at thesupplementnewsletter@gmail.com.

And integrate us into your daily routine over on Instagram.

This week, we’re tackling this question: What does anti-Indigenous racism in healthcare look like in Canada?

TL;DR: A recent independent investigation has documented the staggeringly widespread and deadly nature of anti-Indigenous racism in BC’s healthcare system. Rooted in a legacy of colonialism, this problem is not new or unique to the province. Tackling it will demand “coherent, systematic action,” said lead investigator Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond in her report.

Here’s our answer:

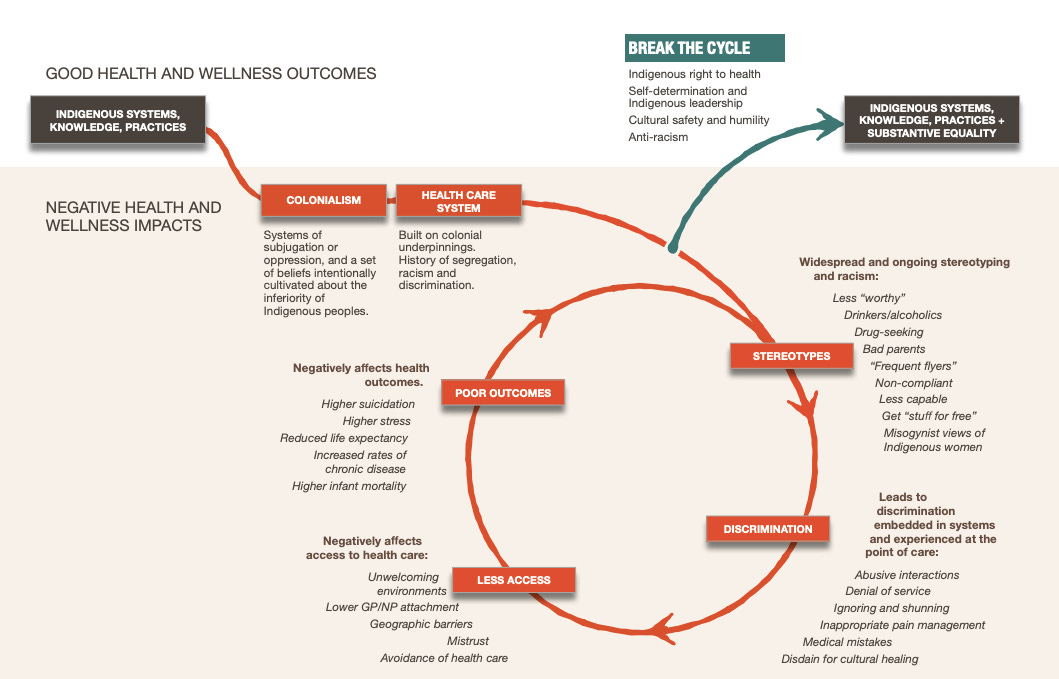

Anti-Indigenous racism in Canadian healthcare is not new — it is rooted in the country’s legacy of colonialism. But let’s start with the most recent news on this issue.

In June, allegations that emergency healthcare workers in some of BC’s hospitals were guessing Indigenous patients’ blood alcohol levels as a game called “The Price is Right” made headlines. That quickly sparked an independent investigation, led by Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, a former judge of Cree and Scottish heritage.

This week, Turpel-Lafond released her comprehensive findings, which drew on the participation of almost 9,000 people.

While she couldn’t substantiate allegations about the “game,” the investigation did document the staggeringly widespread and deadly nature of anti-Indigenous racism in healthcare. Based on the report, 84 per cent of Indigenous participants said they have experienced discrimination based on negative stereotypes and prejudice. The discrimination disproportionately harms Indigenous women and girls — something also reflected in the report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). At the same time, over half of respondents who are Indigenous healthcare workers said they have faced workplace racism.

So when Indigenous people heard about the alleged “game” back in June, some were not surprised whatsoever.

This problem is not unique to BC’s healthcare system.

In late September, Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year-old mother from the Atikamekw nation of Manawan, died while seeking help in a Quebec hospital. She started live-streaming on Facebook before her death, capturing the verbal abuse that she received from health workers while she was in distress. But despite formally apologizing to Echaquan’s family and calling the incident racist, Premier Francois Legault has repeatedly denied that systemic racism exists in the province. In late November, Quebec rejected measures to improve Indigenous health care, dubbed “Joyce’s Principle,” because of its mention of systemic racism.

Another example is the practice of birth alerts. Serving as warnings to hospitals from social services agencies about mothers or family situations deemed “high risk,” birth alerts can lead to family separation and bring more children into the foster care system. In particular, this practice disproportionately impacts and causes harm to Indigenous and Black mothers. But despite a call in 2019 by the MMIWG inquiry to immediately end the practice of birth alerts, some provinces like Manitoba and Ontario did not do so until this year. Meanwhile, birth alerts are still used in Saskatchewan.

Back in BC, Health Minister Adrian Dix has apologized, acknowledged systemic racism and said he will direct the ministry to work on all 24 recommendations laid out in the report.

What remains to be seen is how committed the government will be to their implementation process. As Turpel-Lafond points out in her report, it’s not that there hasn’t been any effort to address anti-Indigenous racism — the problems remain because efforts to do so are “sporadic, disconnected, at times personality-dependent, and not underpinned by strong and systemic foundations.”

“Addressing systemic racism requires coherent, systematic action,” reads the report. “Uprooting Indigenous-specific racism in health care requires shifts in governance, leadership, legislation and policy, education, and practice.”

We could go on forever about discrimination in the healthcare industry and how it doesn’t just affect Indigenous peoples. Write to us with your further questions at thesupplementnewsletter@gmail.com.

Here’s someone to follow:

CBC journalist and columnist Angela Sterritt, who is Gitxsan, is someone you need to follow ASAP for impactful coverage of Indigenous peoples and issues. A household name in BC, Sterritt was also honoured as one of Vancouver’s most influential people this year by Vancouver Magazine.

Here’s a story to check out:

In Mexico, over 66,000 people have disappeared since 2006, and 16 people continue to go missing each day. As the police and government fail to locate them, their families have taken up the search. Follow the families’ dangerous journey to uncovering Mexico’s mask graves with this visually stunning investigation just launched in The Globe and Mail. Bonus: here’s the backstory of that reporting.