How has COVID-19 impacted Canadian prisons?

From last spring's severe outbreaks to the current update on vaccination policy, we catch you up.

Hey there, and welcome to the 14th issue of The Supplement, a newsletter that fills in the gaps of your other news intake. This is Alex, one-third of the Supplement team!

Each week, we pick a question submitted by you, our readers. If you’d like to submit a question for a future week — it can seriously be about anything — then email us at thesupplementnewsletter@gmail.com. Check us out on Instagram, let’s be friends there too!

This week, we’re tackling this question: How has COVID-19 impacted Canadian prisons?

TL;DR: Canadian prisons have been sites of big COVID-19 outbreaks due to their enclosed settings, prompting prison depopulation and the prioritization of vaccinating elderly federal inmates. As this issue continues, we recommend reading beyond daily headlines and consider the systemic factors that form the prison system as we know it today.

Here’s our answer:

Before delving into the question, here’s some key context:

Firstly, Canadian federal prisons hold people who have been sentenced to two or more years, while provincial and territorial prisons hold those who are sentenced to less than two years. Notably, remand prisoners — those who are held in custody but are actually awaiting trial and therefore legally presumed innocent — make up the majority of the population in the latter level.

Secondly, Black and Indigenous people in Canada are disproportionately incarcerated — a disparity fuelled by systemic racism that is only growing. Low-income individuals and people with mental illnesses are also over-represented in the system.

Enter COVID-19.

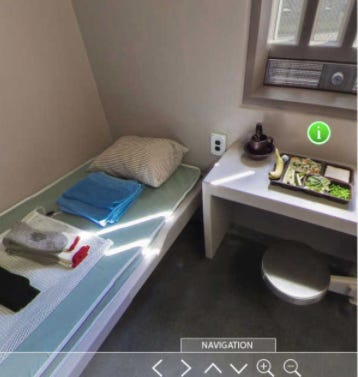

As documented throughout the pandemic, there have been numerous outbreaks in prisons due to lots of enclosed spaces, which make it difficult to physically distance. And attempts to space out inmates have not gone well — Canada’s prison ombudsperson raised human rights concerns in April 2020 about measures to curb COVID-19’s spread that verge on forcible solitary confinement — a practice that amounts to torture, if prolonged. At the same time, there have been allegations of inadequate support, such as inmates not having regular access to necessities like masks and hand sanitizer.

In response, calls for prison depopulation started early, especially for the release of low-risk and non-violent inmates. Since then, the prison population at both levels has fallen, but things have been moving much more slowly at the federal level.

More recently there has been a huge caseload surge, with cases since December 1, 2020 surpassing the total number from March to November 2020.

Inmates are pushing back. Last year, inmates at Toronto South Detention Centre held at least eight hunger strikes protesting lockdown conditions and availability of personal protective equipment — allegations which the Ontario government denied. In January, up to 100 inmates at two correctional centres in Saskatchewan also started a hunger strike to protest the provincial government’s handling of outbreaks and called for Corrections and Policing Minister Christine Tell’s resignation.

Meanwhile, the rollout of vaccines has also added fuel to the conversation around prisons.

Canada has prioritized vaccinating 600 elderly and medically vulnerable inmates, or about five per cent of the federal prison system’s population. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization attributed this decision to the high risk of virus spread and the numerous outbreaks in prisons’ congregate settings. The Correctional Service of Canada is also required to ensure that inmates are given proper healthcare.

But Conservative politicians like Opposition Leader Erin O’Toole have criticized the plan, tweeting, “Not one criminal should be vaccinated ahead of any vulnerable Canadian or frontline health worker.” This statement prompted major backlash from the public and other political leaders (and it’s also worth pointing out that COVID-19 in prisons also impacts corrections staff).

In the meantime, it remains to be seen how different jurisdictions will roll out their vaccination plan for provincial and territorial prisons.

This is part of an ongoing series on the criminal justice system, so send us questions on the topic that you want us to dig into!

Here’s someone to follow:

Ginella Massa is no stranger to breaking barriers. She first made history in 2015 by being the first reporter in Canada to wear a hijab on air while working as a CTV Kitchener video journalist. This week, Massa notched another major milestone as the first hijab-wearing anchor of a national primetime show, “Canada Tonight,” on CBC News.

Here’s a story to check out:

A few weeks ago, we touched on the issue of birth alerts in our discussion about anti-Indigenous racism in healthcare. BC ended the practice in September 2019, but an exclusive story from IndigiNews this week reveals that the province’s lawyers had already warned the Ministry of Children and Family Development about how birth alerts are “illegal and unconstitutional” months before — going back to May 2019.